|

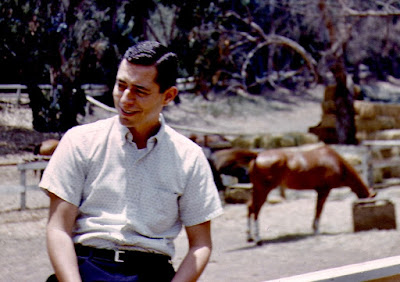

| My Dad at Will Rogers State Park, approximately 1964 |

Unlike me, my dad was a pretty good athlete. When he was young, his favorite sport was basketball. He was the point guard in a competitive amateur league that even played in a tournament in the old Sports Arena. He loved playing softball too, and I spent many Saturdays in the summer tagging along, watching the Times reporters team play against other offices like the District Attorney, or split into Kiddies vs. Codgers.

My dad always encouraged my interest in sports, and if he ever felt disappointed that I was completely lacking in talent, speed, and coordination, he never let it show around me. We spent endless hours tossing the baseball, or the frisbee, or shooting baskets. He was a strong swimmer too, and I loved being in the ocean with him. I wanted badly to be good at baseball; two years in Little League taught me that except for throwing, catching, running, and hitting, I could have been a decent ballplayer.

Like most men devoted to his work and his family, he found it harder and harder to get out and play sports, and he started to get a little paunchy and out-of-shape. I guess it was sometime in his late thirties that he started running, or as we called it then, jogging. He would put on his shorts and head down the to high school track and run a mile, or two, or three. It seemed to be just enough exercise to help him feel like he was keeping in the game. A few times, I tried to run with him but it really had no appeal at all for me. I associated running with P.E. class, and P.E. class with humiliation. But I always admired his consistent effort.

In 1978, a local group started a 10K race in his town, Pacific Palisades. By then I was off starting my own life on the opposite coast, so I didn't pay much attention, but at some point my dad decided to start running the Will Rogers 10K. I guess he ran it about 10 times over the years, and while I have no idea what kind of times he ran I don't think that mattered to him. He was proud that he was taking care of his health and proud to be out there putting in his effort in the race.

The Will Rogers race gets its name from Will Rogers State Park. The first half of the race starts downhill and then climbs, but overall it's fairly flat. The second half, however, turns down the hill on Sunset Boulevard from Chautauqua, until it reaches a wide sweeping curve at the bottom of a hill. Then it climbs a series of steep switchbacks to the park. After passing through the park the course runs down a steep hill and then back up Sunset to reach the Palisades. It's not an easy 10K.

Will Rogers Park was the home of the famous writer and humorist who built a beautiful ranch in the Santa Monica Mountains so he could have a little piece of Oklahoma but still get to Hollywood for his career. When I was very young, my parents started taking me to the park. We'd visit the polo ponies, hike up the hills, and occasionally tour the rambling ranch home of Will Rogers. I was always fascinated by Will Rogers - he seemed so clever and witty, and I loved his home. There was something about his humor and his good nature that I always associated with my father, and when I found out that Rogers had died in an airplane crash the day before my father was born, the connection became even stronger. Will Rogers most famous quote, "I never met a man I didn't like", seemed to me almost as if it was something my father had said.

Despite my father's good nature and his strength and his exercise, cancer proved to be even stronger and he died more than 10 years ago, a young man by any standard. This was a sad recapitulation of his father's even earlier death from lung cancer. It's still hard for me to believe he's not around, and I miss him all the time.

I started running about two years ago. It didn't really have anything to do with my father at the time. I was getting close to 50 and for some reason decided that I ought to complete a marathon. My original idea was just to walk it. As I got stronger in my training, I decided that I'd get there faster if I ran at least part of the time, so that's what I do now - walk some, run some. I'm very slow, but to my great surprise, I love it. After years of frustration and humiliation related to sports, I've found something I really like to do, and the fact that I'm slow doesn't bother me, at least most of the time. I completed that marathon (another story) and since then have run a half-marathon, a 21-mile race, and maybe a dozen 5K and 10K races.

Last week I ran the Will Rogers 10K for the first time, but the earlier part of the week was marked by another event I had promised myself I would complete around my fiftieth birthday - a colonoscopy. I was about a year late, but I got it done, and they even removed a polyp. In theory, a polyp left in is a potential cancer, so removing it might have saved my life - who knows? Just before I went in for the "procedure", the doctor asked if I had any questions; I told him no, but that I wanted him to know that colon cancer killed my father, so I was counting on him to take his time and look around carefully. He wrote this information on the chart with the solemnity it deserved.

Three days later I was out on the course with my oldest good friend Robert. His father hung in longer but died in the last year. We had both run the 5K version of the Will Rogers race, but we were tackling the 10K for the first time. Robert told me he'd run with me, but frankly I'm a lot slower than he is and I didn't want to hold him back. I told him I'd be glad to see him at the finish line.

I hadn't trained for the race very well and by the time I made the turn down Sunset away from the 5K course I was getting pretty tired. It was a hot day too. But it was exhilarating running down the middle of Sunset Boulevard, a beautiful day, a beautiful road and no cars. I began to think of my dad and all the times he had run this route before me. This was the road he'd run, he'd seen the same eucalyptus trees and guard rails and street signs. He was here before me, and now it's my turn.

I'm not one of those people who imagines the dead looking down upon the living and watching them. My cosmology doesn't really permit that kind of sentiment -- my dad was here, and now he's gone, and that's how it is to me. But as I was running down Sunset, and especially as I turned up the narrow driveway that marks the entrance to the park, I had the feeling that my father knew what I was doing and he was proud of me. It may not have made me run any faster, but it did buoy my spirits and I had one of the most enjoyable runs I've ever had.

It was a long way back up Sunset and I was glad to see the end of the race, but I did manage to run through the finish with my arms up and a smile on my face. So what if I was the 932nd runner out of 986? Robert and Lucy and her sisters were there to cheer me on, and like my dad, they encourage me no matter how slow I am. I ran my race, and I'm proud of it. Despite adversity and pain and doubt, my dad ran through the finish line every time, including at the end of his life, and that's one of the lessons I learned from him. Nobody but me knows what it feels like to put out my best effort, nobody will necessarily reward me for it or think much of it, but I can do it Dad, I can do it. I know what my best is and I won't be satisfied with less. He knows that, and he's proud of me.

Michael Berman

July 6, 2008

Postscript: Yes, I still run when I can. Right now walking is what my body wants to do but I will run again as soon as I'm ready.